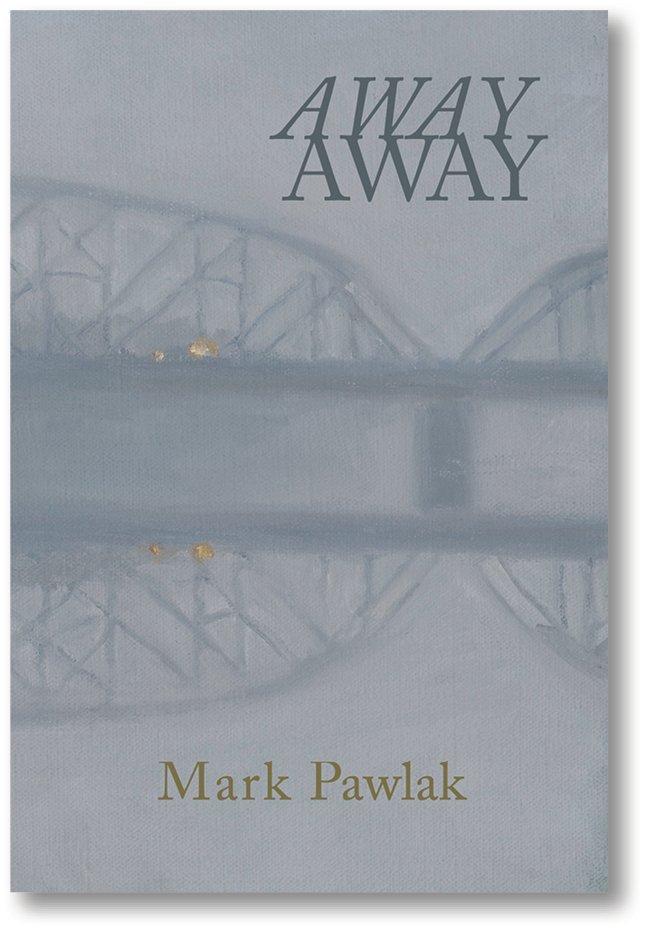

Curated Collections of Images and Impressions: a review of Mark Pawlak’s AWAY AWAY by Carlene Gadapee

Away, Away

Mark Pawlak

Arrowsmith Press, 2024

97 pp.

Mark Pawlak is a poetic diarist; his speaker is an observer/reporter, but not often a participant in the narrative in the poems. Some poems read like travelogues; what is seen is keenly noted and recorded, snapshots laid out for us and catalogued, each observation a stanza. The juxtapositions of (mainly) things seen create both content and context, a “third note” that trends toward a deeper understanding beyond the words on the page. Pawlak’s speaker engages the reader with curated collections of images and impressions, and we are invited to join him on this trip through very recognizable landscapes.

We are on a road trip, a purposeful meander, one that focuses on the esoteric and the sublime found on strange road signs, restroom notices, and other evidence of human habitation. The poem “Hilltown Sartori” takes us on a New England journey, one in which descriptions of iconic images like maples and oaks and sugar shacks are juxtaposed with police log entries: what is beautiful exists beside less prosaic or bucolic things like dead deer, icy roads, and broken-down vehicles, potholes and malfunctioning wood stoves. This is truly New England; perhaps not the one that tourists encounter often, but certainly a recognizable landscape for those of us who live here year-round.

The poem “Thirteen Moons” serves as a lovely amplification of the traditional almanac, creating a richly layered vision that is deeply New England, with such lines as “Garden faucet icicle:/ one crystal droplet, / at its tip/ refracting sunlight” and “Summer yard party: / dusk descends/ insects come out: / some sting, some don’t.” I find myself nodding and chuckling, often sitting back and briefly reminiscing about my own backyard at dusk, or my drenched peonies “bent low by downpours, / cream-white blossoms/ soiled. Soiled!”

I don’t think it’s necessary to be from, or live in, New England to fully enjoy or find a place to put your feet in Pawlak’s poems. While the setting is tangible and location-specific, the experiences of wandering through a familiar and loved landscape and noting both its beauty and its gritty qualities can appeal to readers from just about anywhere. One such poem, replete with regional details and universal concerns is “Backwoods and Maritimes Beauty Tips.” The poem is written in sections, using found language from a primary text; in this case, an old recipe book from New Brunswick. Beauty tips abound: how to rid a lady’s face of freckles, how to darken hair and eyebrows, what to do to defeat wrinkles, and how to remove facial warts. The language is not New England-specific, and neither are the purported concerns that a “genteel lady” might face. The end result is truly endearing and funny, if a little unnerving. Pawlak’s choice of primary text is rich with both authentic language and images from which this poem springs.

The poem “Marx said,” brings a wry smile to my face. Truly, so many small New England towns have declined, almost to a level of being derelict, nearly abandoned. The age of the automobile cut business down significantly in the 1950s, and trains don’t run through many of the small mill towns anymore. The lumber business dried up and paper mills have closed. What’s left is a landscape both ugly and ironically humorous, as Pawlak’s poem describes: “…old neighborhoods / suffer decline / or utter change…// But some things remain: / the after-hours diners, / the street corner watering holes.” The signage mentioned in the poem brings a chuckle, noting how some folks remain brave, even in the face of desperate decline, like the one outside of a strip club: “’ Changing the World / One Lap Dance at a Time!’”

As a counterpoint, the poem “Birthday” presents a lyrical, evocative memory, a sort of ode to childhood and a past that is not only personal but also one that we can all find a connection with. The poem recalls a different time, one spent with a grandparent shopping for Sunday dinner, a live chicken butchered and cleaned on the spot. Images are spooled out in one long ribbon of remembrance: ragpickers, knife sharpeners, canned fruits, hand-me-downs, family events, and “black and white images with scalloped borders / created by a camera….” This rush of memory is followed by telephones with dials, roller-skates, wild places and grasshoppers, local beers and finally, the second-hand cars that needed constant maintenance. While I am not quite the same age as Pawlak, much of this poem and its lovingly recalled images are very familiar to me. This poem invites us into his world, but connects us to our own as well. We can live in the world of this poem alongside the people, things, places, and events; our own past may not be the same street, but it certainly lives in the same neighborhood.

So many of the poems in this collection are traveling poems: walking, cars, riding in trains. The poem “Lake Shore Limited” not only moves very quickly—each stanza is a glimpse out of the train window—but it also slows us down with the images Pawlak paints for us. We see the landscape again, and it is New England-familiar, with shrub pine, maple, sumac, birch, tamarack, etc. Then we see industrial yards, the “back sides of old factories and mills with bricked-up windows” and “dumpsters filled with industrial trash.” Graffiti, school buses, wild flowers, and vestiges of cities and human habitation wink by, but we are left with an overwhelming sense of movement: we are traveling with the speaker on a journey across a landscape that tells us more about the people not in the poem, but who are clearly in the landscape. This poem takes us from South Station in Boston to just outside of Buffalo, New York. We’ve gone many miles, both in the physical landscape and in the telling of the story of New England as well.

The last five poems of Away, Away focus on the recent Covid-19 pandemic. The first of this set is titled “Pandemic Days,” and it is a stark reminder of how spring, with its glorious blossoms and promise, was so starkly undercut by the rise of a deadly illness that no one knew how to cope with, the “flowering of / the sick, bedridden, / the dying, intubated, // the dead.” The next poem, “Lockdown Diary” is very familiar in a lot of ways. I’m pretty sure we all have one, whether it is a physical diary, emails, notes, photos, or just our vivid memories of a sudden paradigm shift that literally took our breath away. This poem is written in small sections, observations of a landscape changed and deserted by most people, except those who had nowhere to go, like “one man, sneakers unlaced” on a city park bench that is taped with caution tape, or those who, being cautious stroll in the park “gloved hand in hand.” The poem is also punctuated by protest posters that capture the resistant mood that permeated all of the fear and caution: “JESUS IS MY VACCINE” and “I WANT A HAIRCUT” are the counterpoint to people who are “solemnly climbing church steps, / …all dressed in black: / bearing a polished metal urn.”

The fifth poem, and the last of the collection, is titled “Aftertime.” The poem brings us back to the main theme of the collection, in that we are all still heading somewhere, whether in the physical landscape or through and beyond the pandemic crisis. We are moving in “incremental accumulations” that are comprised of childhood memories, places we’ve been, where we live, and where we are going next. Perhaps it is enough to say we are going Away Away.

A poet-teacher both by vocation and by trade, Carlene M. Gadapee’s poetry and critical reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in many publications, including English Journal, Waterwheel Review, Gyroscope Review, Smoky Quartz, Think, Allium, Vox Populi, and MicroLit Almanac. Carlene also received a “Best of the Net” nomination in 2023. Her chapbook, What to Keep, will be released by Finishing Line Press in early 2025. Carlene lives and works in northern New Hampshire.