A Journey Without Definite Answers by Carlene Gadapee

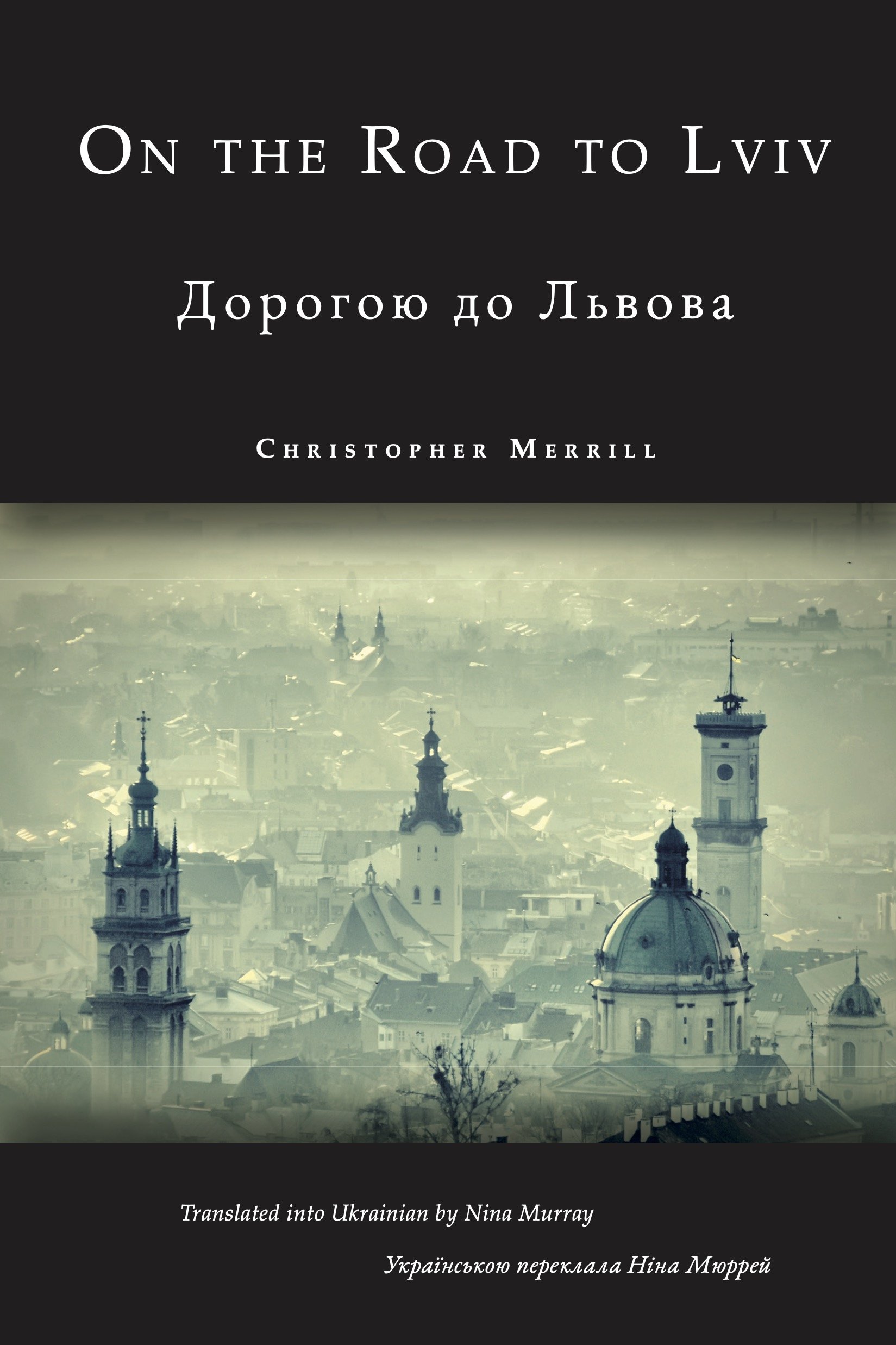

On the Road to Lviv

By Christopher Merrill, translated by Nina Murray

Arrowsmith Press 2023

103 pp.

Christopher Merrill’s On the Road to Lviv follows the architecture of the epic. The poet-speaker follows an external journey in order to confront interior questions. However, in a break from the classic format, by the end of the poem we are left wondering who –if anyone—is the hero, and whether anyone can even be the hero of contemporary conflicts that are rooted in a history of shifting boundaries and betrayed loyalties. Merrill introduces individual voices that represent various viewpoints, and he embeds history and public figures from both centuries and decades past and from contemporary times as well. In this way, the reader is a witness to present-day events unfolding as a continuation of geographic and generational hostility in the setting of Eastern Europe.

The text is replete with historical references that bring both clarity and emotional depth to the current conflict in Ukraine. At times deeply personal, and at others, more detached, this book-length poem serves as both elegy and eulogy for a country that has only rarely been peaceful, and certainly not since the advent of the 20th century and the two World Wars that redefined both political relationships and nations in Europe. Merrill’s poet-speaker provides the reader with necessary history and geography lessons that aid in the understanding of both the text and the ongoing conflict. This becomes the framework upon which the central questions about human dignity and cultural identity are hung.

Merrill’s poem references both Adam Zagajewski and his poem, “To Go to Lvov.” The intentional similarity of the titles suggests the purpose of Merrill’s poem. If Zagajewski’s poem is a paean to a utopian memory-scape, then the brutal scenes in Merrill’s poem must then be the counterpoint, the lived reality in the midst of conflict. When the city was known as Lvov, it was part of Poland. The constantly shifting borders make the name not so much a physical one, but more of a wished-for location. On the Road to Lviv, as a title, does a lot of work. It is not just a location on a map in current-day Ukraine, it is also a wish: a wish to go to a serene place, the Lvov of Zagajewski’s poem, to head in the direction of national identity and security. In On the Road to Lviv, the poet-speaker must leave at the end of his journey without definite answers, and there is no way to understand the brutality and annihilation that is present in Ukraine. In the Zagajewski poem, Lvov is a place to return to when the world is too harsh. The reader can “go breathless, go to Lvov, after all/ it exists, quiet and pure as/ a peach. It is everywhere.” Not so in Merrill’s poem.

The poet-speaker, like the poet, is a cultural diplomat, traveling in Ukraine to help foster cultural understanding. He is there to witness and to observe, not to offer solutions. Merrill uses the poet-speaker to amplify the situation through the use of composite voices that represent various prevailing opinions. In this way, the observations and judgments are not that of one voice; instead, the reader is brought into the world of the text as a co-witness to what is said and seen. Some of the references made in the text may be missed, especially if one is not familiar with the history and geography of the region, or with historical or public figures mentioned. I did some research as I read, and the poem opened up and became a lesson I needed to learn, both as a reader and as a person who is concerned with human beings who are living in conflict. Merrill focuses our attention on the historical and generational conflicts most people are not aware of. In this way, the role of a cultural diplomat is best served; not through a lecture, but through a deeply affective epic poem that presents a culture’s dignity and distress in a way that fosters empathy in the audience.

The landscape of the poem is a hard juxtaposition of almost fairy-tale-like images and a bleak reality: planes, tanks, and tractor-trailers alongside castles and horse-drawn carriages. The story tells of deeply held religious faith and of ethnic cleansing, of both fertile countryside villages and destroyed cities and lives. Merrill uses the epic convention of an invocation to the Muse of History, but he calls the muse “fickle,” saying, “I cannot/ Imagine or invent lives for the peasants/ Glimpsed in this dream of war and independence” – the poet-speaker cannot create this landscape and the images of pain independently, and he requires the Muse’s help in order to tell this tale as a witness to such harshness in a beautiful landscape.

In keeping with epic conventions, the poet-speaker has a female guide who serves in the same way as Dante’s Beatrice. Natalya, a “Foreign Service National,” is not there to provide commentary, but to guide; in fact, she “[i]gnores all questions deemed political, / Including venues, meals, accommodations, / And Russia’s near abroad…and anywhere/ One Russian nationalist can be found.” She will guide him where he needs to go in the physical landscape, but he must navigate the interior one on his own. The poet-speaker is aware of the ambiguity of his mission; his status as a Western visitor is underscored by the behaviors of “democratic-minded Westerners…/ who are determined to develop/ Civil societies around the world--/ Utopians…who may/ Wreak havoc in a quest to undermine/ The power of authoritarians/ To dictate what their people must believe/ In order to survive.” He will have to form his own impressions, always aware of his role as outside observer.

On page 18, Merrill reintroduces Zagajewski by talking about a time when he was reading for a group of poets outdoors who “kept looking up, as if in prayer, / Since poetry is prayer.” This is the central point of the poem: who can speak, to the wider global community and to God, about what is going on in Ukraine? Percy Bysshe Shelley, in his essay, “In Defence of Poetry,” states that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” This is the role of the poet-speaker in On the Road to Lviv. Merrill uses elevated, biblical diction when he says that the poets in Zagajewski’s audience come to “revel in the word made manifest,” and he goes on to say “amen to the poets, then, who savor/ A blaze of words under the chestnut tree.”

The text asks us to consider how we can praise this world, as broken as it is. On page 20, the poet-speaker recounts what is happening more recently in Ukraine, in the Donbas region and in Kyiv. He mentions mercenaries and makes reference to “the strongman in the Kremlin”—any reader who watches the news or reads good journalistic accounts would understand these references. But Merrill’s poet-speaker veers away from the conflict for a space and he speaks of what poets in workshops would rather focus on, things like prosody, form, and diction. In this way, this part of the poem becomes a sort of ars poetica: What is the role a poet should play, and how can poems be crafted to serve? The next section of the poem, then, is all the more jarring, depicting in startling, unpoetic language the form and function not of poems, but of Russian vacuum bombs and the horror and devastation they cause. Those who survive must “pick/ Through their municipality’s debris--/… totaled cars/ Wires, concrete, and shattered glass from flattened buildings, / The cries of children trapped in a cancer ward/ Whose walls are falling in.”

Children appear again in the next section of the poem, where “children from a hospice in Kazan/ stand outside in the snow, in a Z formation, / Fists raised in a demonstration of support/ For the invasion of Ukraine, their caregivers/ Determined not to cry until a drone/ Can take a photograph”—sick children being used as propaganda for the world to see and to demoralize Ukrainians. Z is the symbol for Russian victory, but the poet-speaker questions this: “Or does Z mean the end of everything?”

Merrill uses individual characters’ words to carry the emotional weight of the poem. For example, on page 26, the character Zoya Sheftalovich tweets, “It’s hard to shoot babushka in cold blood.” She has confronted young Russian soldiers who don’t even know what their mission is, and she sends them on their way. Readers know that this is not entirely fiction; it was reported that the young Russian soldiers were given misinformation, but it is more affective and effective to have a character speak to their youth and confusion.

The poem shifts again to the poet-speaker on his journey. He says that there “was no time to visit the monument/ to Adam Mickiewicz…/ Dramatist, and revolutionary thinker,” and it is at this point, more research was needed. Mickiewicz lived from 1798-1855, and he was a writer and revolutionary, a social activist much like others we hear about in the daily news. Not only is the monument a physical landmark for the poem, but the inclusion of Mickiewicz at this point in the narrative serves as a reminder that Eastern Europe is both rich in culture and in conflict, and has endured a pattern of shifting borders and alliances that has bred ingrained resentment and hostility. As the poet-speaker says on page 30, their forefathers’ “faith in a triadic understanding/ Of God, society, and the afterlife/ Would mark the shifting borders of these lands.” Faith and the Holy Trinity have become secularized and weaponized.

In the following section, it is made clear that the West has not really learned from history, taking instead a cultural attitude of “not our concern.” The war in Ukraine is not a new one; in fact, one could easily argue that it is just the next chapter in a very long book of political tension and a fight for national identity. The time period of the Color Revolutions, a series of anticorruption and pro-democracy protests in the former Soviet states between 2000-2010, is the same as the poet-speakers’ first mission to the area; his next was right after the invasion of Crimea and the Donbas region. The poet-speaker recounts the work he was doing in Ukraine at that time, touring museums and leading workshops. He brings Zagajewski back into the narrative almost as a personal talisman, saying that Zagajewski’s poem “would reorient/ My perspective on the past—and the hereafter.”

The narrative is firmly anchored in current events, starting on page 34 with the discussion of Russian attacks on health care facilities and the anti-war protests throughout Russia. I was unclear about who the mystic on page 36 was, and this is where my education about the theory of the Third Rome, and the prophecy about Russian world domination by Baba Vanga began. The “global order” would be rearranged “in favor of authoritarians/ And oligarchs”—chilling to read, to consider, and to now understand where Putin’s perceived mandate is coming from.

The next section of the poem refers to another poet-activist, Taras Shevchenko, who is credited with developing the Ukrainian language and literature. The poet-speaker is at the monument to Shevchenko, and it is surrounded by sandbags. Cultural identity is both literally and figuratively under assault, because most Russians do not acknowledge Ukrainian as a distinct language and do not believe that Ukrainians have a rich cultural heritage separate from Russia. Throughout, Merrill’s poet-speaker weaves international politics and official responses to the current conflict into the narrative, and Merrill further humanizes each situation through a character. For example, there is a “conscript from Siberia/ Who could not bring himself to shoot his foes/ Because his mother was Ukrainian.” The region has a deeply complicated, shared history in many ways; what is this war –this continuation of war—really about? The Russian Orthodox Patriarch blesses the aggression; this is the theory of the Third Rome, that states that the ultimate center of Christianity is Moscow; thus, it is Russia’s destiny to save and rule the world. This would then “usher in a thousand years of peace/ For all who kneel before our Mother Russia!” Clearly, a lot is at stake, culturally and literally.

On page 44, readers are again brought back to the reality of the present with a recounting of the bombing of the Kramatorsk train station, with a missile labeled “For the Children.” This section of the poem raises the question: who will hold Putin and Russia accountable? The poem argues that most Westerners cannot fully understand the situation; the media tells us what they want us to hear, people only believe what they already expect to understand, and little will change their preconceived ideas about problems far away from their own doors. Russian soldiers call their “mothers, wives, and friends” before raping and killing civilians in “villages they occupied and looted” (46). This poem, through the poet-speaker’s observations, reaches the audience in a different, more affective and effective way than the news media can.

The most damning word in the poem is on page 46: “Perhaps.” This suggests that with the enormity of the destruction, the astronomical costs both financially and in human lives, it is unclear how there can be an accounting that will measure all of this fairly, let alone accurately. Even the Russian soldiers were forced to camp on radioactive ground around Chernobyl—the devastation is great, and it is not limited to Ukraine.

So, who should tell the story? Historians often revise events to make things less complicated, the “commentariat” vacillates and shifts the narrative, survivors are terrorized into silence or compliance—is it the poets? This current chapter in the conflict in Ukraine is “[t]he most transparent war in history” because events are recorded in real time, yet even the unvarnished record is often manipulated into forms that don’t reflect what we are sure we witnessed. The poet-speaker tells us on page 52 that the citizens themselves must defend what and who they are, and we should “pay homage to the territorial/ Defenders who not long ago imagined/ Their lives unfolding in much different ways.”

The narrative turns to a pragmatic discussion about Russian material assets (“how many BTGs--/… might/ Remain available for operations/ In Ukraine”) and the conclusion is that Russia is not going to be able to assemble enough soldiers and weapons “[t]o save the Kremlin from disaster. Nyet.” In the next section, there is a dissident playwright who was “jailed on the first day/ Of demonstrations against the war.” This composite character is made up of many dissident artists and writers; this part of the poem then becomes an extended metaphor: war as a tragic play. The poet-speaker says, “[t]he despot ordered them to raise the curtains/ On the next act of a long-running drama/ He was directing from his mountain redoubt, / Critics be damned.” And the people who “believed/ Their tyrant’s every word…slept at night, like babies.” Then the narrative shifts back to religion. The Ukrainian Orthodox Christians wish to separate --for good reason-- from the Russian Orthodox Church. This is a critical component of national and cultural identity, because “prelates everywhere [are] discovering/ Signs of divinity in this disaster….” The arts and faith are attacked, and cultural identity suffers.

We meet an unnamed soldier “holed up/ In the steel factory in Mariupol” who is thinking about a poet and his unfinished work that was collected and catalogued a century before. The soldier was “imagining that if/ The Russian shelling…did not obliterate him he just might/ Translate this book into Ukrainian.” Ukrainian cultural and national sovereignty are threatened, especially from the “genocidal rhetoric of Russian/ Media” which is reporting disinformation about each defeat, warping public sentiment. And as a “military analyst explained/ On state TV,” the Ukrainian people must be re-educated, a task that “might require/ Thirty or forty years to complete.” This would encompass a full generation, and require more violence and conflict.

In the next few sections of the poem, readers meet a film-maker who is in favor of concentration camps and sterilization, more military actions against civilians –children—and some military analysts offering opinions. The question of how Russia and Ukraine could ever come to peaceful co-existence is raised; the “litany of grievances” will come to “supplant/ The liturgy and sacred mysteries.” This question remains unanswered; the conflict predates all of those who consider it.

On page 68, the poet-speaker, in his role as a cultural diplomat, is gathering materials for a lecture and a workshop he will be teaching. This interlude of normalcy is a necessary reprieve from current events. The poet-speaker and the other professors talk about the celebration of Constitution Day in Ukraine, and they are concerned about how May 9th, “Victory Day” for Russia, might play out. Their conversation amounts to well-intentioned hand-wringing and they turn to present concerns, like the “seminar/ For graduate creative writing students/ And what to make of the declining numbers/ In the humanities.” While this may seem like a mundane conversation –and it is, on the surface—it prods us to consider what place the humanities have in a world so torn by political and cultural violence. Again, who is left to tell the story, especially if there are fewer students studying humanities?

From pages 70-72, the poem reads in part like the news account of Zelensky’s speech on February 24, 2022. “Never again” becomes “again,” and we know that the cycle of conflict never really stopped. Because the speech took place on the poet-speaker’s 65th birthday, he states, “I can retire, / …and yet I am compelled to write/ These lines…/ To make a record of my witness here/ Below and justify the ways of men/ and women who prevail against the deeds/ Of evildoers who would kill them all”—Milton’s voice echoes throughout this passage. Milton felt called to “justify the ways of God to man,” and while Merrill isn’t quite so lofty in his chosen task, someone has to write this poem, and it’s his calling to do so. In the text we have two speakers: the poet, and the poet-speaker, an intentional creation of the poet. At this point, the poet has taken over the narrative, and Merrill talks to the reader directly. He provides the historical precedent that is the foundation of Putin’s justification for the current conflict: rooting out Nazis in Ukraine. Merrill also briefly mentions the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, perhaps to provide a time marker, but also to comment more broadly about who has the right to determine the course of any life (74). This short departure from the primary narrative foreshadows a later criticism of the media and its fixation on news from the United States as taking precedence over other international stories.

The war-narrative returns with a list of the horrors perpetrated by “[f]ascism, Russian style, Ukrainians/ Call ruscism—a coinage born of code-/ Switching and the criminal brutality/ Of this special military operation.” The poet-speaker also provides a short history of the Ukrainian language and how brutality and denigration galvanize a people: the Ukrainians defend their language “daily/ In poetry and on the battlefield.” There is brutality on both sides in war, to “humiliate the dead.” No one is entirely innocent.

The narrative turns to the Russian journalists who protested on air, “[o]rdering citizens and oligarchs/ To just say no to war.” Although Putin did not use the Victory Day celebration to declare a wider military engagement, Russian believers were “imagining a victory/ Commensurate with VE Day, this time/ Over Ukraine.” This is followed by another composite character who says the International Criminal Court must prosecute the war crimes, and that there has to be accountability or there will be global anarchy. The poet-speaker, though, makes the point that “whatever verdicts may be rendered/ Will satisfy no one,” especially “idealists who believe/ That justice can be blind even in wartime.” Will war fatigue become too great, and the world –and Ukraine--just have to move on?

When Merrill invites other voices into the poem, it lends a broader credibility, not just to his poet-speaker’s voice, but to the poem as epic narrative as well. Even the voices of Russian supporters are included, which grounds the poem in the complications of lived experience. The italicized voices are not quotes; they function as arguments reflecting real-time discussions. On page 84, there is a “journalist on her sixth war” who is talking about the nature and root cause of war (“the sudden loss of power”) to a group of international humanitarians and diplomats. She offers her opinion on the current conflict and the strategies being employed, and closes with “[s]trategic ambiguity is not/ What Western masters of grand strategy/ Imagine it to be.” There won’t be any winners, and the best one can hope for is to “save our friends.”

The narrative returns to the war, and Merrill embeds more history lessons, explaining that Putin “invoked Peter the Great’s success” as another historical justification for his war on Ukraine. The poet-speaker ends this section with the observation that Putin’s “imperial imaginings, / …may end only with his death.” The next section is an indictment of the international press, that “turned its attention to another story, / Inflation and school shootings….” The news from the United States has taken precedence, and the global audience has moved on. However, the poet-speaker makes it clear that the effects of the war in Ukraine will reach us all; economies are affected, global food and fuel supplies are interrupted, and “[t]o use food as a weapon in a war/ Of unprovoked aggression is a form/ Of evil dating from antiquity.” There is another history lesson that includes a reference to the Holodomor, another Russian-created famine used against the people of Ukraine (1932-33). Putin’s harsh tactics equal Stalin’s, but with an even wider global reach. The poem asks us to consider how Putin can think he’ll ever have any meaningful international respect or support now. On page 94, a priest says that “There’s no water, gas, electricity/ Or faith remaining in our besieged city.” Through this character we get the most scathing indictment of those who turn away because they are tired of hearing about atrocities, and they “must lack the courage, / Will, or interest to remember why/ They promised to deliver in the heat/ Of battle weapons, food, and medical/ Supplies, without which we will not survive….”

The poem returns to the poet-speaker on his travels toward the western region of Ukraine, to Lviv. We meet Natalya again, who takes a photograph which will be filed away with her routine report; this is all pro forma, and her job is almost done. The poet-speaker has shared some sobering personal understandings on this cultural diplomatic trip about Eastern Europe, and of “autocrats and democracy,” but he cannot stay.

There is one more disturbing history lesson about Stepan Bandera, a man who was a cruel Nazi collaborator, a far-right radical Ukrainian nationalist who was posthumously called “The Hero of Ukraine” for his efforts by former (and disgraced) Ukrainian president Yushchenko in 2010. The award was quickly annulled in 2011. Bandera allied himself with the Nazis in order to present a unified front against the Soviets; he was later poisoned by KGB in 1959. The poet-speaker tells us that “[t[ight-lipped Natalya” would not even speak about Bandera’s vision of “pure Ukrainians/ Born of selective breeding and the deaths/ Of Jews.” The past is ever-present in the current conflict in Ukraine.

Christopher Merrill crafts a morally and socially compelling story rooted in both history and current events. The poem both honors and carries Adam Zagajewski’s concerns forward into current lived experiences. The poet-speaker in On the Road to Lviv has to leave behind the ruins and damage done to a nation seeking security and an identity, and he can only achieve perspective through the use of both scholarship and distance. He looks around and says, “Natalya ushered me into the van. / The night train to Kyiv was leaving soon.” The reader is left with the question: Who must tell the story? This text suggests that it is the poets who must speak. The poet-speaker’s journey in Ukraine is done, but the lessons are ours.

Carlene M. Gadapee teaches high school English and is the associate creative director for The Frost Place Studio Sessions. Her poems and poetry reviews have been published by or are forthcoming in Waterwheel Review, Smoky Quartz, Margate Bookie, Wild Words, Allium, Vox Populi, and elsewhere. Carlene resides with her husband in northern New Hampshire.